Organizations helping run the locations for people released from prison warned that without state funding, the centers “won’t survive”

From CT Mirror:

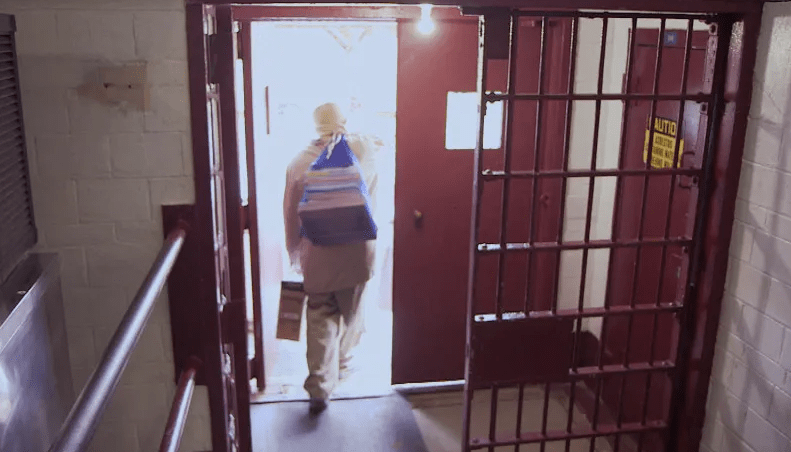

On the verge of having to cease operations due to expiring American Rescue Plan Act funding, Connecticut’s Reentry Welcome Centers are seeking answers about how the state is using the tens of millions of dollars saved by recent prison closures and warning that a lack of investment could result in dire consequences for the reentry community.

On Wednesday, the organizations that help run the reentry centers, places that aid people in finding employment and community services as they leave incarceration, conveyed their need for clarity while expressing frustration that they have not received any of the approximately $26.5 million saved annually by the closures of three prisons since 2021 due to a shrinking prison population.

“Those dollars were supposed to go back to community providers and fund these programs that had great impact in the community,” said Scott Wilderman, the president and CEO of Career Resources, Inc., a workforce development organization helping people leaving prison. “And not one of those dollars was ever recaptured at all by any nonprofit.”

The money saved through prison closures went into the state’s General Fund, said Chris Collibee, a spokesman for Gov. Ned Lamont’s budget office. “There is no implementing language that directs the funds from prison closures to be directed to certain programs,” he said.

Without state funding for the five reentry centers, which are currently backed by private philanthropy and about $2 million expiring federal ARPA dollars, providers said they don’t believe they will have the resources to continue functioning. State agencies must have expended all ARPA funds or have awarded them to outside entities by year’s end.

“They won’t survive,” Wilderman said of the resource centers, located in Bridgeport, Hartford, New Britain, New Haven and Waterbury.

Responding to questions from lawmakers about the funds last week, representatives of the Department of Correction said the savings had already been subtracted from the agency’s budget. Rep. Toni Walker, the House chair of the legislature’s budget writing committee, indicated that the panel would request from the governor’s budget office a breakdown of how the money was used.

“We need the state support, critically,” said Judy McBride, the director of strategic partnership investments for the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving, which has helped fund Hartford’s reentry center, on Wednesday. “That’s not to say we won’t continue to try to do what we can, but it’s bigger than any one entity.”

Legislators and community organizers have spent much of the last year discussing how to provide adequate reentry services for people in prison — a much broader endeavor that advocates say should start as early as pretrial.

Last year, the state announced the closure of Willard Correctional in Enfield, making it the third facility to close since 2021, following Northern Correctional in Somers and Radgowski Correctional in Montville. Advocates then held a press conference in Hartford’s Legislative Office Building to speak out about their desire for the state to allocate the roughly $26.5 million saved annually to people reintegrating into their communities.

During last year’s legislative session, officials passed a measure aimed at fixing loopholes in a 2017 law requiring the Department of Correction and the Department of Motor Vehicles to provide state ID cards or driver’s licenses to people being released from prison.

Connecticut Voices for Children, a research and advocacy organization, later released a report recommending that the state turn to people leaving incarceration to help combat an ongoing workforce shortage.

People in prison said they were without adequate programming to aid in their rehabilitation, possibly making it more difficult for them to prepare to reacclimate to their communities upon release. The state also began erasing the criminal records of tens of thousands of people convicted of misdemeanors and low-level felonies.

Entering this year’s legislative session, which convened earlier this month, Gov. Ned Lamont pointed to the fact that people would need “fewer second chances if we give them more first chances” in his annual State of the State address.

On Wednesday, the reentry center organizers and lawmakers introduced their 2024 State of Reentry Report, providing data on the people leaving or nearing the end of their incarceration.

Among its conclusions, the report found that 93% of people incarcerated on June 1, 2023, with sentences ending within six months, struggled with substance use, while 37% had a moderate-to-severe mental health disorders.

about:blank

It found that of those released from incarceration between June 1, 2022, and May 31, 2023, 14% went from incarceration to immediate homelessness, according to data provided by the DOC. It also identified low levels of high school graduation rates and limited employment histories.

Sen. Tony Hwang, R-Fairfield, said he believes the data provides targets for the legislature to address, particularly in the areas of housing, health and employment.

“I think a basic theme is, ‘Good people make mistakes,’” Hwang said. “And I think we have a social as well as a humane responsibility to create pathways for people to be able, who have paid their mistakes, and to move on forward.”

Rep. Christopher Rosario, D-Bridgeport, said he sees reentry centers as the places where “everyone’s journey begins.”

“That’s where everyone gets set on that path on how you redo your life, how you right those wrongs that you did,” said Rosario, whose brother, Virgilio, was formerly incarcerated. “And it’s important that we, as policymakers, when we get these reports, when we legislate and we’re at the Appropriations Committee, that we fund those programs.”

It was because of “interacting with those who give you an opportunity to kick doors down” that Kenny Jackson said he was able to transition from “Jackson 86853,” his assigned number as a Connecticut prisoner, to now being Dr. Jackson, a national financial literacy instructor.

“Some of the things that I was deprived of, now I motivate,” Jackson said. “And some of the same issues that men and women used to look up to me on the negative, now they respect me because I’m a beacon of light on the positive.”

For some people, the reentry centers are their reentry services, added Beth Hines, the executive director of Community Partners in Action, which helps run the Hartford and Waterbury locations.

“So what will happen to people coming home from prison if we don’t exist?” she asked.